Everything You Wanted to Know about Publishing a Picture Book (But Didn't Know Who to Ask):

Part 4—Publishing

If you've

followed the instructions in the first three articles in this series, you

should now have the text and the illustrations you’ll need to indie publish a

picture book. Great! This last article

will show you how to combine all these elements into pdf files that you can

upload to

CreateSpace, so you can

finally publish your book.

Create the File for

the Interior of Your Finished Book

Until now,

you've probably been creating or scanning and manipulating artwork in a

pixel-based art program, like Adobe Photoshop (the industry leader) or Corel

Photo-Paint (what I use, because it’s great and much cheaper than Photoshop).

At this point, you'll probably want to transfer your illustrations to a

vector-based design program, like Adobe Illustrator or CorelDRAW. This will

make it easier to turn your illustrations into a multi-page PDF, which is the

format your book will need to be in so you can upload it for publishing.

Click File

and then New to create a new document in your vector-based design program and

format it to fit the correct size, number of pages, color format (CMYK), and

dpi (300) for your book. Here’s an example of a file setup from CorelDRAW for a

40-page book with an 8.5” by 11” trim size:

Import your

finished artwork page by page to the correct page it’s meant to go on in the

finished book and fit it so that it exactly fills the page. (Using “Snap to

Page” can help you make sure that you reach the edges exactly.) Once you've

done this for all of your pages, save the document before continuing.

Insert Text

Open your

Word document with all the lines of text for your story (as well as the

copyright page and any other extra pieces of text that are going to go into

your book) already formatted in the font, size, and leading that you want in

your finished book. As I mentioned in the

second

article of this series, I asked my writing friends about font size, and

most of them said that 16 was the right size font for picture books. I went

with 20, because anything smaller seemed to disappear on the page, but 16 is

certainly acceptable. It’s also recommended to use a san serif font, like

Helvetica or Arial, for picture books, because younger eyes find these simpler

fonts easier to read. (I chose Arial Rounded, because the rounded look seemed

to fit the fairy-elephant look that I was going for.) A wide leading (space

between lines) also makes text easier to read, so a leading between 1.25 and

1.5 should work well. Copy and paste each piece of text from Word into the page

it’s meant to go on, and then save the file again.

Layout Your Book

Make sure

text is legible and contrasts with the background. Make text on dark

backgrounds light, and make text on light backgrounds dark. If the background

has a variety of colors, it might help to put a partially see-through dark or

light background between the text and the part of the illustration where the

text goes. You can also use the opposite of the color that’s in the background.

For example, if the background is dark blue (which is a combination of cyan and

magenta), yellow is the color that will best make the text stand out.

When I was a

layout artist for a newspaper, I learned that black and red don’t work well

together. Give it a try, and you’ll see how red text seems to disappear against

a black background, and black text seems to disappear against a red background.

Switch one of the colors for white or yellow, and you’ll also see how much

better these colors work with black and red.

Add the text

for the inner title page, copyright page, and any other extras that are meant

to go into the book (like a dedication, a note about the author, or added

information about the book or other picture books by the same author). Except

for the copyright page, convert each finished page into a bitmap. (In CorelDraw

X7, for example, that requires clicking on Bitmaps at the top, and then “Convert

to Bitmap” on the top of the drop-down menu.) Once you do this, the text (as

well as drop shadow and any other elements) will become a fixed part of the

illustration. Later on, you won’t be able to undo it, so don’t convert your

pages to bitmaps until you’re absolutely sure the page is the way you’re going

to want it in the finished book, text included. I recommend saving the file every time you

convert a page to bitmap, just in case the program crashes at any point. It

probably won’t, but large 300 dpi files take up a lot of memory, so it’s best

to play it safe.

You can also

convert the file containing your cover, back cover, and the spine of your book

to bitmap, although I highly recommend you first give it a new name, so you can

still make changes to the original file later on if necessary.

The

copyright page has to be done last, because it will need to include the ISBN

that CreateSpace will give you later on.

Alternatively,

if you don't have a vector-based design program, you can select all of the

objects on a page and then hit “combine all objects” in your pixel-based art

program. I suggest doing it the other way, because most pixel-based programs

don’t let you create multi-page

documents, which means you'll have to insert each page into something like Word

before you can convert it into a PDF. There is, however, one advantage to doing

it that way: Amazon Kindle prefers Word documents to PDFs, so creating your

file in Word might make it a little easier to convert your print book to an

e-book. Either way, you'll have to reformat all of your pages later on to fit a

Kindle, which means you'll have to convert all of them to RGB color at 96 dpi

and the right size for Kindle, which is 800 by 1280 pixels for all of Amazon’s

color Kindles to date. (Black-and-white Kindles use a different format, but it

makes more sense to format a full-color children’s book for the Kindle Fire) There

are, however, much easier ways to format a picture book for Kindle. Download

Formatting Children’s Books and Comics by

Charles Spender (the fifth file on the list you'll find

here)

to learn more. Another option is to use Kindle Comic Creator, as this video explains:

Creating a Picture Book

Using Kindle Comic Creator. CreateSpace does allow publishers to publish to

Kindle easily, pretty much with just the click of a button—but I have learned

from experience that this doesn't work with full-color, fully illustrated

books. It’s just best to format and publish your print book and your Kindle

ebook separately.

Why, you

might be asking, must you convert all your pages to bitmaps or “combine all

objects” on each page? You have to do this because it will lower the size of

your book’s interior PDF file. That’s important, because CreateSpace can only

take interior files that are less than 400 MB. That might seem like a lot, but

30 or more pages at 300 dpi with layers can really add up. Combining layers

into one bitmap makes the file a lot smaller, so you can upload it to

CreateSpace.

Publish It!

So now you have almost everything you’re going

to need to put together those two PDFs and publish your picture book! You still

have to get an ISBN, and you’re going to have to put it on your book’s

copyright page. You can buy your own, but CreateSpace will give you an ISBN for

free, and using CreateSpace’s makes it easier for CreateSpace to distribute

your book to more markets.

Sign in on

the left, or click on the orange “Start a title for free” button if you don't

have an account yet and need to create one.

Once you've

created an account and logged in, you'll be taken to your dashboard, which show

“My Account” on the left, your member ID number, the CreateSpace Message Center

(where you can find the emails that CreateSpace has sent you), your royalty

balance for the current month, a list of your books with their ID numbers and a

place you can click to order copies, and information about how many copies each

of your books have sold so far this month. (Yay, I just found out I sold

another copy of

Why

My Love Life Sucks! Thanks, paperback purchaser with excellent taste. You

just made my day.) Click on the button that says “Add New Title” near the top

middle of your dashboard. Or if you've already started creating your book,

click on the book’s name. This will take you to the Project Homepage of that

title.

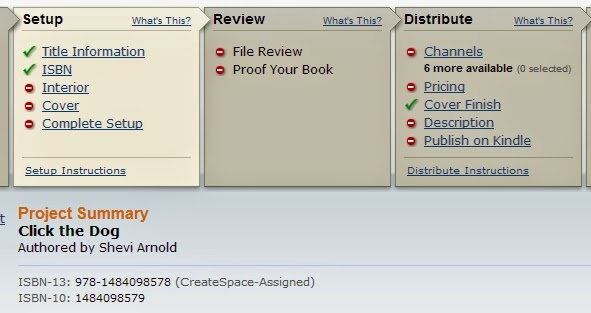

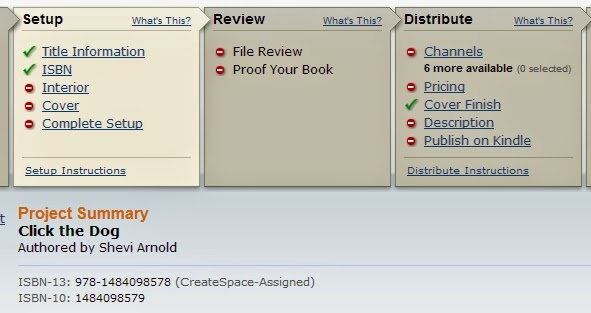

Here’s one for a picture book I'm working on called Click the Dog:

Let’s ignore the Create and Sales &

Marketing sections for now and focus on the three columns in the middle: Setup,

Review, and Distribute.

|

| This shows the Project Homepage of a picture book I’m working on called Click the Dog. The green check marks mean that I've completed these stages. The red circles with white lines mean I haven’t done these yet. And anything marked with a clock icon is currently under review with CreateSpace. Note: once you have acquired a CreateSpace ISBN for a project, you cannot change the ISBN for that project. |

Click on

“Title Information” under Setup. Fill in the required information on the next

page (you can tell it’s required because it has an asterisk after it). This

includes your book’s title, the primary author, and the Language of your book.

You’ll also want to click on the drop-down menu for “Add Contributors” to

select “Illustrated by” and then click on the blue “Add” button to credit the

illustrator, too. Look over all the other fields to see if there’s anything

there that you need to fill in because it’s relevant to the particular book you’re

publishing. When you’re done with that, click on the blue Save & Continue

button at the bottom of the page. This will take you to the next page, which is

the one where you can add your own ISBN (if you have one and want to use it) or

get an assigned CreateSpace ISBN.

|

Setup, Review, Distribute, and Sales & Marketing pages on CreateSpace have this on the left. Here it is with the Setup menu open. This makes it easy to access the particular page you need to go to while you’re working on a book. You can make changes on almost anything while you’re still setting up your book, except for the ISBN. The ISBN remains fixed after CreateSpace assigns you one.

|

Once you

have your ISBN, you can copy and paste the number into your copyright page. And

once you've done that, you can turn that page into a bitmap. And once you’ve

done that you’re now ready to turn the file of your book into a PDF. Yay!

The

vector-design program you’re using may have three ways to do this.

1. You might

see a “Publish to PDF” option in the File drop-down menu.

2. There

might be a PDF option in the Print menu.

3. And you

might be able to choose PDF as a format under Export.

Whichever

way you do it, make sure to check all the options to verify that your PDF will

have 300dpi, be in CMYK, and (if that’s available) made up of bitmaps. Once

you've published, printed, or exported to PDF, open your PDF file in a PDF

reader to make sure that it looks the way you want it to. If it doesn't—for

example, if it's in grayscale or the illustrations don't go all the way to the

edges of the page—go back to your file, try to create a PDF again (possibly

using a different method), and try to see where you might have gone wrong.

Eventually you should be able to create a PDF that’s exactly the way you need

it to be. You’ll also need to create a PDF of the file with your book's front

cover, back cover, and spine. (For more information on creating this file,

check out the

article

about illustrating in this series. You can also check out the CreateSpace

article on

formatting

your book's cover.)

Now that

you've created the PDFs for your book's interior and its front and back cover,

you’re ready to move onto the next step: uploading your book's interior.

Select “Full Color” under Interior Type, and then click on “Choose a

Different Size” to select the trim size for your book. Then select “Upload your

Book File,” click the blue Browse button, find the PDF of your book’s interior

that you created, and double click on that.

You'll be asked to select whether or not you want the interior pages

to bleed. “Bleeding” means that the artwork will go past the trim size, so that

when the book is trimmed, the artwork will go all the way to the edges of the

page. For most picture books, you'll want to click on “Ends after the edges of the page.” Leave “Run automated print checks and view

formatting issues online” checked. Scroll down and click on the blue Save

button. Your book should now upload. This step will probably take several

minutes, since you are going to be uploading a rather large file.

When it's done uploading, you'll have the opportunity to review the

file online. Look over each page very carefully to see if there's anything

you've missed. There could be a missing period or a word accidentally written

twice. Maybe the text doesn't show up against the background as well as you'd

like it. Use the double page view to check how the odd and even pages that will

go together look side by side. Make sure that everything is exactly how you

want it—because if it isn't, this is the last time you'll be able to easily fix

what needs to be fixed.

The

Interior

Reviewer will automatically tell you about certain issues, like if parts of

your books are less than 300 dpi, and which pages have these issues. Make sure to click on each issue so you can

figure out what needs to be fixed and where. If anything does need to be fixed,

you’ll have to upload a new file. Jennifer from CreateSpace put together

a list of the

top 10 file specification challenges publishers seem to run into when trying

to upload their books and covers to CreateSpace’s website, so you might want to

check it out if you run into any issues.

|

| The Interior Reviewer from "Members' Top 10 Specification Challenges" from the CreateSpace forums, article by Jennifer, CreateSpace PrePress. Here you see what happens when an image appears to be placed too close to the edge of a page. |

When the Interior Reviewer no longer finds any issues and you're

completely satisfied with how your picture book looks online, click the blue

Save button at the bottom. If you don't see a Save button at the bottom, try

uploading your book's interior with a different browser. I ran into this

problem with Chrome, but everything was fine when I switched to Firefox.

Once that's done, it's time to save your work and move onto the

cover. You can go there by clicking the blue Save & Continue button at the

bottom or Next at the top or of the Interior page. You can also go there by

clicking on Cover under Setup on the left.

Select glossy or matte. (I don't recommend ordering a sample copy,

since this will not be a copy of your book and it will cost over $6 with

shipping, but that is an option.) If you're not sure which to choose, look at

picture books that you have at home or from your local library. Do they have

glossy or matte covers? If you see both kinds, which do you prefer? I went with

glossy, because that seems to be standard, and I like the way my cover came out,

but it's up to you.

Now it's time to upload the PDF you made with your book's back cover

on the left, the book's spine in the middle, and the book's front cover on the

right. Under “Choose how to submit the cover of your book” select “Upload a

Print-Ready PDF Cover.” Click the blue Browse button, find the PDF of your

cover on your computer, and double click on that.

The maximum

size for your print-ready PDF cover is 40 MB, and if you converted your file to

a bitmap (or combined all objects in a pixel-based art program), your file

should be below that. Once you've successfully uploaded your cover, click Save

& Continue.

This will

take you to Complete Setup, where you'll be able to check everything over and

then submit your book for review. Once you've done that, you'll see a little

clock icon next to File Review on your book's Project Homepage while

CreateSpace is reviewing it. When the review process is done, that clock icon

will turn into a checkmark. You can then order a proof of your book. It's

highly recommended that you do so, but if you’re in a hurry and you're

absolutely sure the book looked perfect when you reviewed it online, you can

skip this stage. I did that with

Fay Fairy’s Very BIG Problem,

because I needed copies of the book for a street fair and couldn't afford to

wait. (Unfortunately, it still didn't arrive in time.) The book looked exactly

as it did when I reviewed it online, so I don't regret skipping this stage. Your

book's proof will look almost identical to what your finished book should look

like, except that it will have a page in the back with the word “proof” written

in huge letters.

And now

you're ready to set up your book for distribution. Yes!

I'm going to

speed through this last section, because—unlike the process of putting your

book together, converting it to a PDF, and uploading it—it’s mostly

self-explanatory.

You’ll start

by selecting distribution channels. You’ll probably want to select all of them:

Amazon.com, Amazon Europe, CreateSpace eStore, Bookstores and Online Retailers,

Libraries & Academic Institutions, and CreateSpace Direct.

Some of these channels are only available to those with a CreateSpace supplied ISBN, which is another reason why you’ll probably want to use theirs instead of buying your own.

One thing

worth noting about the CreateSpace eStore is that you can give people the link

to your book's page there, along with a discount code that will let them get

your book for less. For example, if you go to

https://www.createspace.com/4807674

and enter the discount code

JHCCQCWM, you can get Fay

Fairy’s Very BIG Problem for 30% less than the retail price. For the most

part you'll be buying your own books at cost, which is currently $3.65 for a

40-page full-color picture book, but the link and discount code might be useful

if you're trying to give a wholesaler, bookstore, or school a special deal. Of

course, you can also purchase the books yourself at cost and have them shipped

either to you or to the wholesaler, bookstore, or school.

Once you've selected your book's

distribution channels, it's time to set the price. CreateSpace takes all the

guesswork out of this, by telling you what the minimum list price is for your

title is in US dollars, British pounds, and Euros. It also tells you how much

you'll be making in each of the distribution channels based on the prices

you've set. While it might be tempting to set your price high so you'll make

more money for each copy sold, be careful you don't price yourself out of the

market. Paperback picture books tend to be cheap. On the flip side, don't worry

if the minimum list price seems too high. Amazon and other retailers (excluding

CreateSpace's eStore) will almost certainly sell your book at 10% or more off

the retail price.

Finally, you enter the required

information in your book's Description page. This includes the book's description

(up to 4,000 characters and with limited HTML coding, but watch out for

problematic characters, like apostrophes and ampersands); the BISAC category of

your book (probably a subcategory of Juvenile Fiction), which you’ll select

from a menu; your author biography (up to 2,500 words about your qualifications

or reasons for writing this particular book); the recommended grade reading

level for the book; the book’s language and country of publication; and the

five most relevant search keywords for your book.

And that is how you indie publish a

picture book with CreateSpace.

I hope you've found this helpful, and if you have (or if you still have questions), I hope you'll let me know in the comment section below.

Happy writing, illustrating, and publishing!